Arend termination checker

The need for termination checking in Arend stems from two main problems:

-

Under the Curry–Howard correspondence, recursive calls to a theorem within its own proof correspond to inductive reasoning in classical mathematics. It is essential that such recursive calls are well-founded—meaning they must follow a valid induction schema and avoid circular reasoning.

-

Any system based on dependent type theory would become inconsistent if it allowed nonterminating functions like

\func foo : Nat => suc fooIf such a function were permitted, one could derive False (for example, deducing it from suc (foo) = foo).

The Arend termination checker relies on the following two sufficient criteria for termination:

- the existence of a termination order in the style of Abels’ FOETUS, see this paper;

- the size-change termination principle of Lee, Jones, and Ben-Amram, see this paper.

This page outlines the main steps of Arend’s termination checking algorithm and is intended as a guide for users who encounter termination issues in their Arend code.

1. Detection of Circular Dependencies

The first step made by the Arend termination checker is to detect circular dependencies in definitions. Since Arend does not allow coinductive or nested inductive types, recursion in functions and theorems is the only possible source of non-termination.

- If a group of functions/theorems call each other, a directed graph of function calls is constructed.

- In this graph:

- vertices correspond to functions/theorems,

- edges correspond to calls.

(If function

fcalls functiongtwice in its implementation, then 2 separate edges are constructed.)

- Every strongly connected component (SCC) of this graph then is analyzed on the next stage of the termination checking algorithm.

In particular, if a function/theorem is defined recursively and does not rely on mutual recursion, the resulting graph has only one vertex, and the number of loops on that vertex is the number of different recursive calls inside its body.

2. Preparation of Call Matrices

Once a graph of recursion is found, the next step is to analyze how the arguments evolve in recursive calls. This information is encoded by means of call matrices.

The set of comparison results

Denote by R the set {“?”, “=”, “<”}. This set encodes possible comparison results between function parameters and call arguments. These labels should be read as follows:

- “?” = “no information”

- “=” = “same”

- “<” = “less than”

Call matrices in Arend’s termination checker

After a strongly connected directed graph of calls is constructed, the termination checker assigns a call matrix to each call (i.e. each edge of the graph).

The algorithm responsible for this is run during the type checking phase. During this phase it makes no distinction between explicit and implicit parameters: all function arguments are already inferred, and expressions are normalized with implicit parameters filled in.

For clarity, we assume that all parameters and arguments of functions are explicit.

Let:

-

f have parameters x1, …, xn,

-

g have parameters y1, …, ym.

Suppose that, after normalization and deduction of implicit arguments, the body of f contains a call G = g z1 … zs, where each zj is an expression referring to parameters x1, …, xn and pattern variables introduced by eliminating xi. To this call we associate a call matrix C = C(G) of dimension n × m:

-

Rows correspond to parameters of the caller f (n rows).

-

Columns correspond to parameters of the callee g (m columns).

Each matrix entry Cij belongs to R. Conceptually, it expresses how the argument zj relates to the caller’s parameter xi.

To begin, each parameter x1, …, xn of f is assigned a pattern Pi. This pattern represents the form of the parameter xi in the current elimination clause of f. If the call G appears outside any elimination clause, then Pi is simply the variable pattern xi.

The termination checker tracks variable elimination only inside function bodies defined with \elim or \with.

These elimination constructs may occur only at the top level of a function or theorem definition.

As a result, nested elimination blocks do not arise, and the patterns Pi never need to be computed by repeated pattern substitution.

The exact value of Cij now computed from Pi and zj according to the set of rules described below.

First of all, if the j-th parameter of g is not supplied (i.e. j > s), then set Cij = “?”.

In what follows assume j ≤ s.

If the pattern for xi is a variable (i.e. Pi is just xi), then Cij = “=” if zj is exactly a reference to xi, otherwise, Cij = “?”.

Now suppose Pi= c q1, … qk is a constructor pattern of some data type D with subpatterns qr.

Exact match

First, the checker attempts to match the argument zj directly against the whole constructor pattern Pi:

- If zj is a call to the same constructor c and all its arguments match the subpatterns q1, …, qk (recursively using the same rules), then Cij = “=”.

More precisely, if the list of constructor arguments of zj matches the list of subpatterns, and all component comparisons return “=”, the whole comparison returns “=”. If some component returns “<”, the whole comparison returns “<”. If some component returns “?” or there are too few arguments, the result is “?”.

Match with a subpattern

If Pi is a constructor pattern, the checker also attempts to check if zj matches some subpattern of Pi.

For each subpattern qr of Pi, with type Tr, the checker attempts the following procedure:

-

Strip off applications from zj expression until it becomes a plain constructor call

Starting from e0 := zj, the algorithm performs following simplifications:

- if e is an application e’ u, replace it by its function part e’;

- if e is a Σ-projection or field projection e’.n or e’.foo, replace it by e’;

- if e is a path “at” expression p @ a, replace it by the path argument a;

- otherwise, stop.

The checker records the sequence of eliminators that were performed in a list, denote it E.

-

Replay the eliminations on the type of subpattern

Starting from the type Tr of the subpattern qr, the checker applies eliminators recorded in the list E backwards:

- For a Π-eliminator, it requires T to be a Π-type and moves to its codomain (or the Π-type with the first parameter removed, in the case of multiple parameters).

- For a Σ-eliminator selecting component n, it requires T to be a Σ-type and moves to the type of the n-th component.

- For a path eliminator (coming from a p @ a expression), it requires T to be a path type and moves to the underlying “family” type.

- For a class-field eliminator selecting field f, it requires T to be a record/class type and moves to the type of the field f (with the appropriate “this” substitution). Arrays are normalized at this point so that their class representation is visible.

If at any step the current type does not have the expected form, the procedure aborts for this subpattern qr.

-

Check recursion

After replaying all eliminations, suppose the resulting type is T’.

-

If T’ is a data call which is a recursive occurrence of D (or of one of its mutually recursive relatives), then e is considered a recursive subterm of the original argument corresponding to qr and the procedure goes to the next step.

-

Otherwise, the procedure for this subpattern aborts.

-

-

Compare the “stripped-off” expression with the subpattern

If T’ is recursive for D as above, we recursively compare e with qr.

- If the comparison result is either “=” or “<”, then we conclude that zj is strictly smaller than Pi and set Cij = “<”.

If this procedure fails for all subpatterns qr, then the checker cannot establish any comparison results, and it sets Cij = “?”.

Special case: arrays

In constructor patterns for arrays, the length component is not considered a recursive argument, whereas the “tail” (the third component) is.

In terms of the algorithm above, this means:

- when comparing the arguments of a

::pattern against the subpatterns, the checker skips the length component when looking for a structural descent; only the element and tail components are candidates for producing a “<” result.

Formally, when matching a call to :: with 3 subpatterns, the comparison loop over

arguments/subpatterns starts from index 1 (element) rather than 0 (length).

Current limitations: the detection of eliminations

The termination checker detects variable elimination only in \elim and \with clauses that appear at the top level of a function or theorem definition.

Eliminations that occur inside \case expressions are ignored, even if a bare variable is eliminated and even if the \case \elim version is used.

As a result, if a variable introduced in a \case block is used as an argument in a recursive call, the corresponding entry in the call matrix will be “?”.

Tuples, records, and classes

When a parameter of a function has a Σ-type (tuple), record, or class type, and the corresponding argument at a call site is:

- a tuple literal (for Σ-types), or

- a

\newexpression (for records/classes),

then the checker attempts to analyze the components or fields separately.

This means that the call matrix is filled component-wise, rather than treating the entire tuple or record as a single opaque argument.

3. Termination criterion 1: existence of a termination order

This criterion is only tried if the strong connected component in the call graph consists of only vertex, i.e. one deals with a recursive function and not with mutual recursion. Otherwise this step is skipped and Termination criterion 2 is tried, see below.

Let f(x1, … ,xn) be a function that makes m different recursive calls to itself. Each call is represented by an n × n call matrix c1, …, cm.

We say that f admits a (lexicographic) termination order if there exists a sequence of parameter indices i1, i2, …, is, where 1 ≤ ik ≤ n such that the following conditions hold:

- For every call cj, the diagonal entry cji1, i1 is either “<” or “=”.

- Let I1 be the set of all j for which cji1, i1 = “=”.

- Restrict attention to calls with indices in I1. For each j ∊ I1,

the diagonal entry cji2, i2 is required to be either “<” or “=”.

- Let I2 be the those j from I1 for which cji2, i2 = “=”.

-

Continue in the same way: at stage k, look only at calls indexed by Ik-1. For each such call, the diagonal entry at position ik must be “<” or “=”, and define Ik as those with “=”.

- In the end Is is empty, i.e. at the last chosen parameter all remaining calls decrease strictly.

The question of whether f admits a termination order can be restated more compactly in terms of matrices:

- For each call matrix cj, keep only its diagonal entries and discard the rest.

- Collect these diagonals into an m × n matrix, where each row corresponds to the diagonal of one call matrix.

A termination order for f exists iff the columns of this combined matrix can be reordered so that it takes the following staircase form (where “*” denotes an arbitrary entry):

< * * *

< * * *

= < * *

= < * *

= = < *

.....

It is clear that a function that admits a termination order is guaranteed to terminate. Indeed, every recursive call strictly decreases its arguments in a fixed lexicographic order: the first parameter where a difference appears becomes smaller, while all earlier ones remain unchanged. Since each parameter is drawn from a well-founded domain (e.g. inductive type), and the lexicographic product of well-founded orders is itself well-founded, infinite descent is impossible, so the recursion must eventually stop.

If termination criterion 1 succeeds, the Arend termination checker will accept the one-vertex SCC and will not do anything else. Otherwise, it would try to compute the completion of the call graph and will try to check if Termination Criterion 2 holds.

4. The Call Graph and its completion

At this stage, we have constructed a call graph:

- Vertices correspond to functions/theorems.

- Edges correspond to calls between them.

- Each edge is labeled with a call matrix describing how the arguments of the callee relate to the parameters of the caller.

Looking only at the call matrices of individual edges is not enough to guarantee termination. For instance, every edge in the graph might contain a “<” entry somewhere, suggesting that some argument decreases on every call. At first sight, termination may appear plausible.

Yet this local evidence can be misleading: when arguments are carefully traced around an entire cycle of calls, it may turn out that no single argument decreases consistently, and the cycle can loop forever.

To rule this out, the termination checker builds the completion of the call graph, in which call matrices are composed along all paths inside the graph. This completion captures the net effect of each cycle on the parameters of every function, making it possible to distinguish genuine structural descent from misleading local decreases.

Matrix composition

We equip the set R = {“?”, “=”, “<”} of comparison results with a semiring structure:

- Addition

+represents taking the “best possible” relation (union of evidence). - Multiplication

*represents composing relations across successive calls.- Composing “<” with “<” or “=” yields “<”.

- Composing with “=” preserves the other relation.

- Composing with “?” loses information.

Operation tables:

+ | < = ? * | < = ?

------------- -------------

< | < < < < | < < ?

= | < = = = | < = ?

? | < = ? ? | ? ? ?

Matrix dimensions

The dimensions of each call matrix are determined by the number of parameters of the domain (caller) and codomain (callee).

If an edge e ends in a vertex v, and another edge f starts from v, then: the number of columns of Ce coincides with the number of rows of Cf.

This suggests we can define the matrix product Ce * Cf (with the usual matrix multiplication formula but using operations of R described above). The resulting matrix describes the evolution of arguments after following first e and then f.

Call graph completion

The completed call graph is obtained by finding all possible compositions of edges and computing their labels (products of call matrices). Since there are only finitely many different call matrices between any two vertices, the completion graph can be computed in finitely many steps.

In categorical language the completed call graph is the subcategory generated by the original call graph (considered as a subgraph of the category in which vertices are functions and hom-sets are sets of call matrices of appropriate sizes).

Current limitations: performance constraints

Calculation of the call graph completion is potentially a heavy computation.

Suppose we have a recursive function on 9 arguments

f (x1, x2, …, x_9)

and it makes two different kinds of self-calls:

-

Cyclic permutation (A)

The function calls itself by rotating the arguments in a 9-cycle: f (x9, x1, …, x_8)

-

Swap of the first two arguments (B)

The function calls itself by swapping only the first two parameters, leaving the others unchanged: f (x2, x1, …, x_9)

Together, these two kinds of recursive calls generate a subgroup of the symmetric group S9: the 9-cycle and the transposition generate all permutations of the 9 arguments. From the point of view of size-change termination, this means that completing the call graph (or closing the size-change graphs under composition) can produce a large number of distinct permutations.

For this reason the Arend termination checker will stop the computation of the completion and will reject the SCC as nonterminating if at least 100 different loops are generated at least on one call graph vertex.

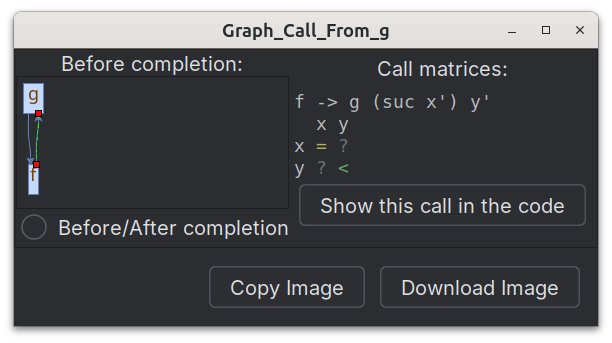

Visualizing the call graph

In Arend, recursive functions/theorems are marked with

- Clicking the icon opens a dialog window in which the call graph is visualized.

- Clicking an edge of the graph displays its call matrix.

- A Before/After completion checkbox switches between showing the call graph before and after the completion operation.

5. Termination criterion 2: size-change principle

The final step of the algorithm is to apply the size-change termination principle to the calculated completed call graph.

For each vertex v in the SCC component, we inspect the resulting idempotent matrices labeling a loop at v of the completed call graph.

The component is accepted if in every idempotent call matrix M labeling a loop there is a (“<”) on some diagonal entry.

Intution behind this sufficient condition is the following. Every infinite call sequence generates an idempotent loop matrix eventually (essentially, this follows from the pigeonhole principle). If every idempotent matrix contains a < somewhere, then some parameter position experiences infinitely many decreases along each infinite sequence of calls, which guarantees termination.